Have you ever looked at the sea of words that humans generate every day – hell, maybe just the sea of words that your company or team generate every day - and said to yourself, “Isn’t there some way to useALL that data for something?”

Yeah, you, me, and everyone else.

Our collective infatuation with extracting useful data from all these words is the modern equivalent of lying on the hood of our dad’s white 1977 Ford Thunderbird wondering about how vast the universe must be or how many stars are in the sky or whether there’s life out there somewhere or what it all means.

Or whatever make and model of car it is you’re lying on in your personal telling of that story.

But you do have that story. Even if you never once looked up at the stars with wonder, you would have that story because you are surrounded by people who have told you that story and because you live in a culture in which that story and others like it comprise a fundamental thread. It’s not a matter of memorizing the words. You know what it means when someone says they were lying down and looking up at the night sky. Even if you never thought about it in these terms, I’d be willing to bet you knowhow to use it to affect another mind. You know without thinking how referring to the story might make another human brain feel a certain way, think a certain idea, imagine a certain thing, or even remember a certain experience. Even just now, maybe an image of what it means to gaze at the stars popped into your mind.Maybe you aren’t entirely sure if that image was from a memory or a movie you watched or a story someone else told you, and now you’re a little irritated at me for making you doubt your own memories.

And yet everything I described to you just now has practically nothing to do with how most of the people who are trying to transform words into data are trying to do it.

The whole natural language processing, machine learning, alternative data source, and AI ecosystem is great at capturing a lot of things, but by and large it is terrible at capturing meaning.

It’s a strange thought, isn’t it? We each possess a powerful and natural capacity for language and storytelling, but most of our efforts to turn words into something that can be used in commercial, research, or investment applications end up effectively abstracting away the meaning of the stories we tell in favor of three other things that are MUCH easier to measure but infinitely less useful: topics, sentiment, and AI slop ‘executive summaries’.

You’ll hear me rail against the problems with all three on these pages in the coming months, but the tyranny of topic plagues more unstructured data analysis tools, products, vendors, and techniques than anything else. And it’s not close.

Imagine for a moment that you wanted to know when people within that sea of words were talking about the infinite vastness of space, or when they were thinking about the personal importance they derived from nostalgic moments with family and friends, or when they were specifically recollecting an experience like the one I described on the hood of a ’77T-Bird. Did it make them happy or sad? Did they feel other things? Did it make them do other things? Did they describe the importance of those things?Did they connect the ideas that occurred to them with other experiences?

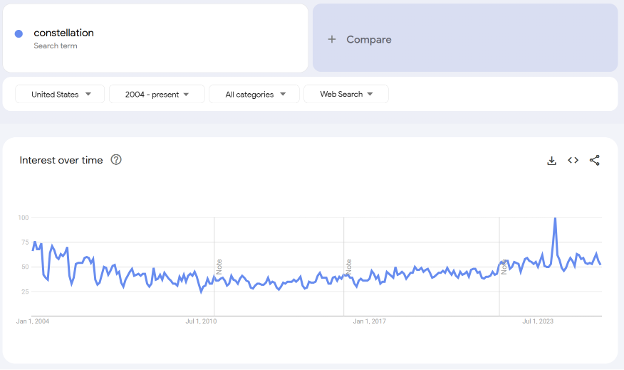

Most of the tools out there these days can tell you that people Googled the word ‘constellation’ a little bit more this week. I’m sure you’ve seen one of these graphics before, usually in a Substack that’s going to extrapolate it into a half dozen conclusions the data don’t support.

But this doesn’t answer your questions. It doesn’t even offer a path to answering your questions! Some of the problems are clear. For example, there are a lot of things which use the word constellation butaren’t about the kind of constellation you’re looking for. The most useful looking data point on this chart, for example? That’s the season finale of the terrible2024 Apple TV science fiction series Constellation, when everyone hitGoogle to figure out what the hell the ending meant.

The little spike in 2025? That’s when The Wine Group announced that it had bought several big-name wine properties fromConstellation Brands.

And what’s the deal with the strong seasonality pattern you can see throughout the chart? The dip months are June, July, and August. Why would there be a dip precisely when star-gazing is easiest in much of theUnited States? The same reason searches for “mitochondria” and “photosynthesis”spike in October and November, respectively: kids are bringing homework home and they and their parents are going to the internet for help. Search term trends are usually a neat party trick, but that doesn’t mean they are useless.Still, whatever meaning they convey clearly is not the meaning that we were looking for.

Now, let’s assume that we figured out how to make sure we were finding only the right kind of references to constellations. That really is a doable thing these days, by the way – rarely perfect but close enough for government work. But we still might miss some bits of text that use different words and terms. After all, star-gazing isn’t always focused on playing connect-the-dots with stars, especially now that you’re just as likely to see one of those weird Starlink trains.

There are plenty of ways to capture more text that probably line up with the questions you want to answer. The easiest is just to add more search terms that you can think of. Stars! Supernovas! Nebulas! Existential Dread! Telescopes!

Alternatively, you can use tools like semantic search to do that work for you in a (usually) more intelligent way. Despite the name, semantic search is largely still lexical matching, a fancy way of saying that it tries to include all the stuff that means basically the same thing as whatever you said. Don’t get me wrong, it’s quite useful for first pass work(i.e. finding texts that probably have some stuff you want). But for all the yeoman’s work sunk into curating graphs of synonyms, domain-specific relationships, and other explicit mappings, most semantic search ontologies are basically just simple search bicycle with a cool thesaurus duct-taped to the handlebars.Semantic search isn’t built to find the dimensions of meaning that you’re looking for here.

You could also use an embeddings model, which instead of presupposing relationships, finds the tendency of certain words and phrases to be in the same neighborhood within texts. You don’t need a human to encode cosmos≈ universe. Instead, the embeddings model determines that relationship statistically by evaluating and comparing huge volumes of text itself. As you might imagine, this feature can make the approach even more flexible, since it doesn’t require that you know all the different ways that someone might talk a bout the thing you have in mind, and it also doesn’t require that someone else has populated a hierarchy of relationships among terms to establish those identities before you’ve even begun.

With an embeddings-based approach, you would typically generate or source a sample text that looks very much like what you’re trying to spot.“Looking at the night sky makes me think about God,” or “The vastness of the universe makes me consider my own mortality,” or “Stargazing is one of those common human experiences that unite us.” Using a measure called cosine similarity, you’d then measure how similar various texts are to these seeds using all those embedded word and phrase relationships we generated before. If the measurement passed some arbitrary threshold you determined, then you would probably call it a match.

Yet embeddings-based models are still built on the geometryof word co-location and frequency. For anything approaching the kind of semantic complexity that exists within the meaningful stories we tell about businesses, economies, art, politics, sports, faith, food, travel, and justabout anything else under the sun, embeddings models struggle almost as mightily to correctly identify good matches as simple search and semantic search. Why?

Because the loudest features of similarity-basedcalculations are nearly always topical features rather than semantic features.

They do not tell you when a certain meaning is present. They tell you when certain nouns are present and - if you’re lucky – when they are co-located with some other words.

In the case of simple and semantic search, co-location of words is explicitly the objective function. You’re looking for one or more words you chose (or which someone curating a semantic hierarchy chose)that exist in the same location! It is exceedingly rare that the literal co-location of words alone will truly define the meaning of the story, framing, or idea you’re looking to identify.

In the case of embeddings-based models, co-location of words is an emergent tendency of the method. The gravity of the mass of words needed to establish that a certain topic is being discussed is so strong that the lightness of words which utterly change the affect, valence, or very meaning of the language used is often lost in the wash. Idiomatic or uncommon language can often utterly destroy its utility, too.

While there are solutions to this narrow case, to help illustrate the point, think about a technical narrative you were looking to identify in a sea of words like, “Gold is likely to be the best hedge against surprise inflation.” Now, based on what I’ve told you about how most embeddings models work, consider how they would score a lexically similar statement in another text which is not semantically similar at all, like “Silver is likely to be the best hedge against surprise inflation.” Most models will see those sentences as near-identical because the framing is identical; they very likely have insufficient context to recognize that you're talking about two potentially diametrically opposed ideas. Again, there are fixes to narrow problems like this, and newer efforts in these areas deal well with simple syntactic problems like negation (finding implicit and explicit “nots”). But implementing them at the scale of the broader lexical/semantic gap problem is like trying to plug holes in a dam with your fingers.

The inevitable next step in the path for those upset with the limited capacity of these approaches to capture semantic complexity is to attempt to train their own model around the linguistic ideas they are trying to track. The result is usually worse! At least with embeddings you are usually creating a large network of lexical relationships (some of which do carry some semantic value). The training of a model around a narrow concept – even with hundreds of examples – is instead oriented around finding the cheapest, most powerful mechanism to discriminate good matches from bad. For the vast majority of narrow training exercises, there is no mechanism for discrimination that will be cheaper or more powerful than topic-defining nouns and its most frequently associated and co-located words!

It would not be difficult at all to argue that an exhaustive, n-gram-based method for defining as large a number of explicit search strings as possible would often be a much better solution for detecting semantically complex ideas than ANY of these methods which will tend to converge on topical features. That kind of method, at least, allows you to construct explicit phrases that actually mean what you mean with a very lowType 1 (false positive) error rate. You can capture “The moon seems brighter than usual” instead of just crossing a threshold of joint similarity to or co-location with “moon” and “brightness.” Indeed, this was precisely what we did ourselves here at Perscient until a few years ago.

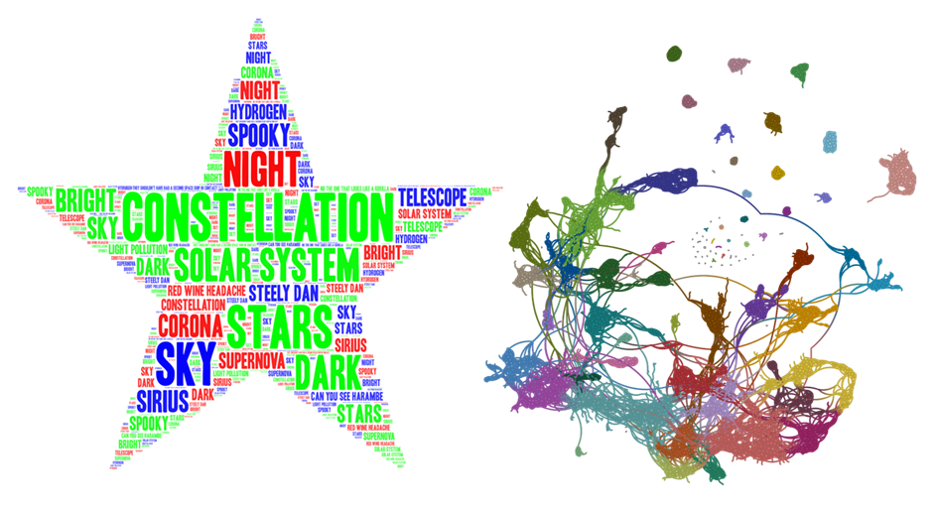

The tyranny of topic creates problems across the range of“AI-based” analytical and data products out there. Sometimes these products are presented to you in the form of unsophisticated slop like the familiar word cloud visualization on the left. Sometimes they are presented to you in theform of more sophisticated connection-driven images like the network graph visualization on the right. But make no mistake – the heart and soul of each of these visualizations and products is the measurement of the frequency of similar nouns and a list of other words you might find near them. All those lines and colors on the chart on the right are the result of edge weights and k-nearest neighbor rankings built on the foundation of topical features derived from cosine similarity.

They are not without their uses – we are friends with the company that produces the chart on the right. We like them. We pay for their product. But it’s not a tool for understanding the meaning of the stories we tell, much less for identifying their presence in the wild.

The reason for the tyranny of topic is simple. Language and storytelling are vastly complex symbolic systems of interconnected, culturally mediated meanings that co-evolved with the human brain. The lexical co-location of words and the context provided by an ontological system like semantic search cannot house those systems. Embeddings loadings lack the dimensionality to contain those systems by orders of magnitude. A small language model cannot possess anywhere near the semantic depth or context of these systems.

But a large language model? A large language model can do that. It can topple the tyranny of topic.

Or at least it can come very, very close. I’ll talk about how and why on these pages soon. But first, I think we need to talk about the other two most common data-from-text product archetypes: sentiment grading andAI executive summary slop.